Malaysia’s political landscape in 2025 was defined by a paradox of consolidation and compromise. Two years into its mandate, the Unity Government, led by Prime Minister (PM) Anwar Ibrahim, has traded its initial platform of sweeping institutional reform for a strategy of political survival within a fragile, ideologically diverse coalition. The government’s moral authority on anti-corruption—a cornerstone of its election mandate—was significantly dented by developments in high-profile corruption cases that were seen as concessions to political allies. Most notable were the partial pardon of former PM Najib Razak in February and the June 2024 High Court dismissal of the Malaysian Bar’s bid to challenge Deputy PM Ahmad Zahid Hamid’s Discharge Not Amounting to Acquittal (DNAA). These cases signalled a willingness to prioritise coalition stability over the rigorous application of the rule of law, fuelling a perception that justice is negotiable for the politically connected.

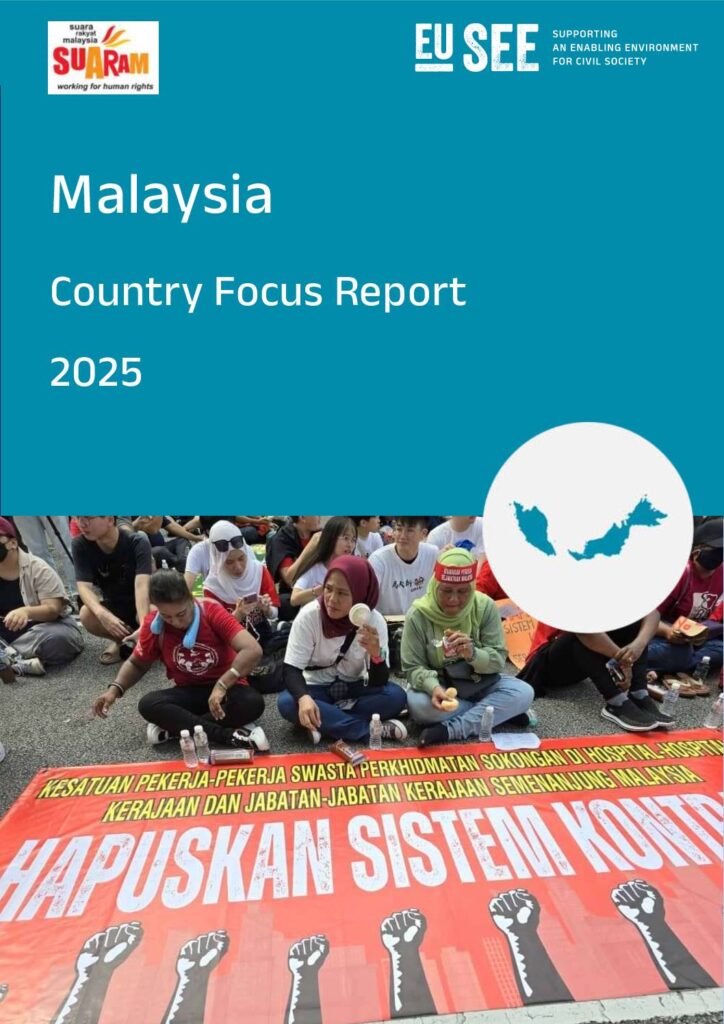

The Madani administration has adopted a conservative stance to manage 3R (Race, Religion, and Royalty) narratives, relying on the aggressive enforcement of existing laws such as the Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act. Moving beyond reactive censorship, the government adopted a proactive regulatory model, introducing a mandatory social media licensing framework and passing a raft of amended and new laws that grant the state far-reaching power to define and remove “harmful” content with minimal to no judicial oversight. Moral policing also remained the status quo, exemplified by the Home Ministry’s raids on bookstores and the seizures of ‘undesirable’ publications under the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984. Furthermore, the environment for freedom of assembly remained restrictive, with the police continuing to weaponise the Peaceful Assembly Act (PAA) and other laws to investigate organisers and participants of peaceful assemblies. Collectively, these developments have kept Malaysia’s civic space rated as “obstructed” by the CIVICUS Monitor.

While the government has maintained a rhetoric of institutional reform, progress on key structural changes has been largely performative. The long-promised separation of the roles of the Attorney General and the Public Prosecutor (AG-PP)—critical for preventing executive interference in prosecutions—remains in the study phase, with a full transition not expected until 2026. Similarly, efforts to safeguard the rights of marginalised groups, including LGBTIQ+ individuals, migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, have largely stalled or regressed. Instead of legal protections, these communities faced heightened risks of arrests and detention, and were targets of mis/disinformation campaigns.

Civil society organisations (CSOs) in 2025 occupied a space of precarious engagement. While the government has increasingly invited CSOs to provide technical input on draft policies and legislation, this is undermined by a parallel environment of intimidation in which risks of investigation, arrest, and surveillance remain status quo.